I have wanted to shave my hair since high school, when I met a beautiful, free-spirited friend who sported a perpetually shaved head. I have decided to shave it now because, after finishing my PhD at Stanford and having my first child, I now know that I can take on much more than I had imagined, and I’ve been trying to put everyday fears aside.

I’ve been attempting the things I have always wanted to do, but have been too afraid to try. Following one lifelong dream, I tried out for a punk band, failed, and then helped form my own. On the career front, I aimed my thesis paper for the highest impact journal and negotiated for a bigger salary. In general, I have been working to live a life free of the fear of things that don’t warrant my fears.

Additionally, as a parent, I have been working to teach my little son to trust himself, to distinguish between the crucial, elemental fears that help him to survive and the useless fears that prevent him from living a life full of boldness and new experiences. I am preparing to teach the same to my in-utero daughter someday. All of this to say, it was time to face the fear of exposure I had always felt at the thought of shaving my head.

After reading my sister’s brave and honest post about the experience of shaving her own head, I started to think more about what that fear signified for me. It wasn’t only aesthetic or practical. I don’t often worry about being insufficiently feminine, and pregnancy has gotten me past many of my fears of a dramatically changing body or appearance.

What I fear is being seen by others as dangerous, untrustworthy, or unfamiliar in a threatening way. I realized that I have worked hard to keep up the appearance of normalcy, modeling my career, aspects of my personality, and my relationships to avoid appearing too “fringe”.

Why? Because when I was 14, after periods of major depression and a few destabilizing manic episodes with elements of psychosis, I was diagnosed with bipolar disorder. At the time, I was told by people whom I loved and trusted that having a mental health label would mark me forever as an “other”, unlike the people around me, and this planted the seed of the shame I have carried about my diagnosis.

Compounding this, before learning to manage my disease, I was outwardly marked by it. In middle school, when everyone was striving for normalcy or a way to fit in, my lack of impulse control and sometimes erratic behavior made it hard to cultivate and maintain friendships.

High school was easier – I found a niche that fit my unpredictability, learning to channel it into a type of apparent fearlessness that attracted friends. But the cost was a perception by my peers that I could not be trusted, that I was flaky and spacy, that I had chronically poor judgement. My erratic behavior led one friend to quietly ask another why I constantly acted like I was on drugs.

In addition, I was cutting myself regularly, but trying to hide the scars from friends and family. I wanted to be perceived as “fun crazy”, not “crazy crazy”. This continued into early college, culminating in flunking out of my freshman year and a suicide attempt that landed me in the ER for several days, first unconscious, then incoherent. This prompted an intervention by my panicked family that resulted in a several month stay in a dual treatment rehab clinic for mental illness and drug abuse. Afterwards, I spent several years in and out of inpatient psychiatric treatment facilities.

For the first time, I recognized that people I loved were afraid for me. Their fear felt like a daily burden, and I was determined to turn things around and show everyone that I was fine, that I could function and take care of myself. However, after several years of stability, I had an extended period of psychosis that introduced a new, more deeply internalized fear.

At the time, I was working as a teaching assistant to middle schoolers, struggling to keep myself together and trying to reconcile my irrational thoughts and feelings with the real world around me. Years of hearing terms like “bipolar” used to describe someone unstable and irrational, of hearing stories of young people with mental illnesses doing dangerous and violent things, of media and popular culture feasting on tales of unstable women who harmed their partners or children, had left me with the sense that I might be someone who could not only be feared for, but be feared.

Now I felt that I could no longer trust myself and my perceptions, and I became convinced that if I were exposed, people would literally be afraid of me. After recovering from this psychotic episode, I found a medication that provided long-term stability, discovered running as a way to dampen the remaining highs and lows, and went back to school to become a scientist.

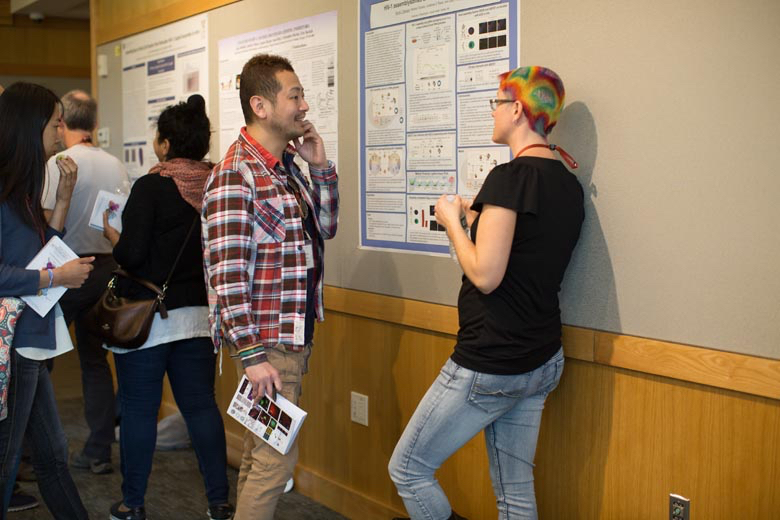

(photo Constance Brukin)

I now work in a profession where dependability and trustworthiness are my most essential assets, one that relies on careful and methodical thought and analysis. In addition, I have become a parent, one of the greatest responsibilities a person can undertake, one that requires consistency, self-control, and again, trustworthiness.

I am privileged that by now my disease is, for the most part, hidden, that I can pass unnoticed through most of my life. But when a senior scientist with no knowledge of my diagnosis makes jokes to colleagues about my “having a mood disorder”, or when I make errors that call my dependability into question, I feel panicked and unmasked.

Similarly, dyeing my hair has always seemed a bit risky and potentially unmasking, but it is increasingly socially acceptable. To be a woman with a SHAVED dyed head seemed to represent a much more dramatic non-conformity, a way of renouncing societal norms and intentionally standing out as someone who goes against unspoken rules of fashion and gender. It seemed like something that could out me as fundamentally different from those around me.

I did it anyway. Here is why, and here is what I have learned. First of all, while for practical reasons I must still sometimes tread carefully when talking about my mental illness, in shaving my head I am renouncing the shame of this disease.

I am powerful, I am a survivor. My experiences have given me a perspective that is unique and important. As I have increasingly outed myself, I have met women who share my symptoms as well as the fear of what their disease will mean to others in their lives. THEY are powerful, THEY are survivors, THEY have taken their lives and transformed them into enriching, successful, connected existences that anyone would be glad to call their own.

Like me, every one of them has been afraid to talk about their own experiences, and every one has been inexpressibly grateful that someone else is talking about theirs. We are afraid of owning one of our greatest accomplishments, surviving and thriving with this disease, because we live in a society that questions womens’ emotions, experiences, and perceptions, and pounces on any excuse to invalidate them.

Like me, every one of them has been afraid to talk about their own experiences, and every one has been inexpressibly grateful that someone else is talking about theirs. We are afraid of owning one of our greatest accomplishments, surviving and thriving with this disease, because we live in a society that questions womens’ emotions, experiences, and perceptions, and pounces on any excuse to invalidate them.

My beautiful naked head symbolizes a shedding of my fear of who I am, and a symbolic shedding of the fears of all women with this disease and other mental illnesses, of the stigma that keeps all of us (your friends, your neighbors, your parents, siblings, and other relatives, and maybe even yourself, millions of your fellow Americans, over one billion people on this planet) hidden away from the world cowering in fear of discovery. As the brave, beautiful, and bipolar Carrie Fisher demonstrated with her words and her example, we are all many things; for some of us, one of them happens to be mentally ill. Or, as Walt Whitman wrote, “I contain multitudes”. I am a mother, a scientist, a runner, a musician, a wife, a sister and daughter, a friend, and someone with bipolar disorder. And I am not afraid.

Check out Brook’s Transformation from a few months back HERE.